US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is conducting a two day workshop on Content of Premarket Submissions for Management of Cybersecurity in Medical Devices on January 29th and 30th.

US National Telecommunications and Information Administration has been facilitating a discussion on Software Bill of Materials as a part of its Software Component Transparency policy development effort.

A question on the table for both of these efforts is what exactly should a Bill of Materials

contain?

The basic presumption here is that when you get a blackbox which could be a medical device, or some app, or a software, or a cloud service, or a hi-tech gadget, having a list of technical ingredients that went into making that blackbox may help make it transparent, trustable, and mange its cyber security or privacy risks. The list of ingredients is called a Bill of Materials or a BoM or SBoM (Software BoM) or CBoM (Cybersecurity BoM).

What is a "material" in a Bill of Materials?

A material is anything that would affect the content, properties and functionality of the blackbox in question. In other words anything that "matters" to the risks associated with a blackbox. A risky material (such as tainted license, insecure code, patent infringement, privacy violation) is likely to make the end product risky to consumers. The risk may not always be transitive.

As a simple example, suppose there is a software application helloworld.exe. It was made using source code helloworld.c, a Makefile that tells how to build the software and make 3.4 command and GCC compiler 1.2.3. The Bill of Materials for helloworld.exe would look like:

helloworld.exe

helloworld.c

Makefile

make 3.4

GCC Compiler 1.2.3

How does such a bill of material (BoM) allow us to identify cybersecurity risks?

Let us assume that the GCC compiler 1.2.3 was infected with a malware that added a backdoor to every executable it created. Now by knowing that helloworld.exe was compiled with this infected compiler one can identify it as a backdoor risk in our IT assets.

What other information should a Bill of Material contain?

At the minimum a bill of material should contain some way to identify every material that is being listed. This may be also known as key, locator or ID information. Since there are multiple identifying schemes (also known as domains, namespaces) in the real world, we need one field to encode the namespace, and one field to encode the name (id, key, locator) that is valid within the namespace.

Examples:

1) Namespace: "commonly known as", Name: "OpenSSL 1.1.1a"

2) Namespace: "cpe", Name: "cpe:2.3:a:openssl:openssl:1.1.1a:*:*:*:*:*:*:*"

3) Namespace: "purl", Name: "pkg:npm/foobar@12.3.1"

4) Namespace: "sha-1", Name: "f1d2d2f924e986ac86fdf7b36c94bcdf32beec15"

5) Namespace: "iTunes", Name: "us/app/vlc-for-mobile/id650377962#?platform=ipad"

6) Namespace: "GooglePlay", Name: "org.videolan.vlc"

6) Namespace: "github", Name: "openssl/openssl/releases/tag/OpenSSL_1_1_1a"

7) Namespace: "uspto", Name: "US7046802B2"

8) Namespace: "spdxid", Name: "SPDXID-12345678"

9) Namespace: "ietf", Name: "RFC8446"

A single software entity may have multiple namespace-name tuples associated with it.

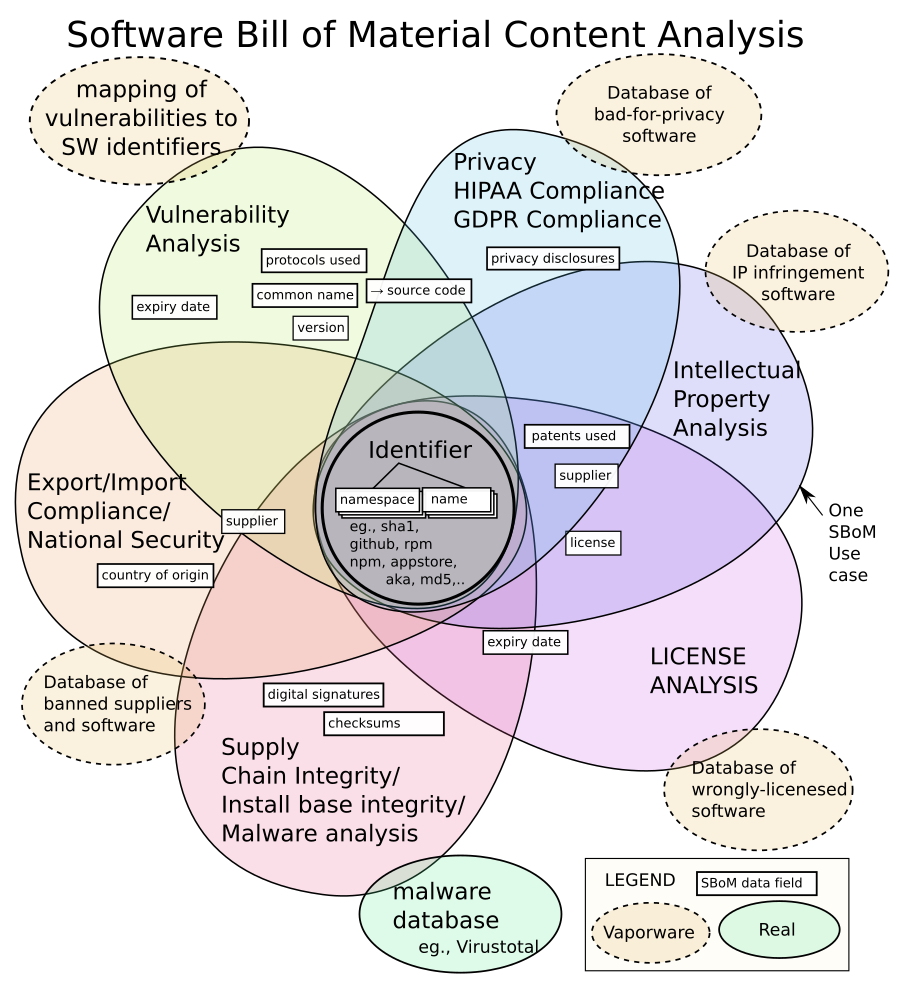

Different use cases need different metadata or SBoM content associated with the software entity as illustrated below:

|

| SBoM/CBoM Content Analysis based on use cases. |

For eg., if the use case is to block software from suppliers that US government thinks are national security threats you would need the names of suppliers of every software entity in the product, but may not care about other fields.

If the use case is to check licenses to answer "am I entitled to use this for commercial purposes?", one needs to know the name or type of licenses included with the software, but may not care about the version numbers.

The things in dotted line bubbles are vaporware (may or may not exist).

For eg., if there was a precise and complete mapping of software entity identifiers to vulnerabilities, we would not need any other fields in the SBoM at all for vulnerability analysis cyber security risk management use case.

Almost all use cases of SBoMs follow a pattern of checking against a "no-fly-list" or a database that maps different risk types to software.